While many organizations focus on climate change, few recognize urbanism as a solution. Green building, renewable energy, and technological solutions alone will not sufficiently address climate change or the related and pressing issues of social justice, affordability, access to opportunity, and the public health crises. Rather, urban growth and development policies must be integral to technological solutions, social programs, and policies within a holistic solution space.

To address this need, Camille Annette Cortes, one of DPZ’s young designers, and DPZ Partner Matt Lambert established PLACE Initiative to focus on solutions intersecting urbanism, climate, and equity — making urbanism and social justice top-level climate priorities.

PLACE stands for Proactive Leadership Advocating for Climate and Equity, an acronym created by DPZ Associate Xavier Iglesias to represent the role that physical design and social systems play in advancing sustainability and economic and social resilience in both urban and rural places.

Clarifying these interconnected topics, PLACE has developed resources and policy recommendations to spread awareness. PLACE has also focused on the overlooked opportunities presented by climate migration. These solutions, whether in a place that is shrinking or experiencing in-migration, a place heavily impacted by climate change, or one barely impacted, require coordination among various organizations, policies, and scales of government.

To address this complexity, PLACE has focused on outcomes through key principles and detailed goals at each level of subsidiarity — from individuals to neighborhoods, communities, governments, and non-governmental entities.

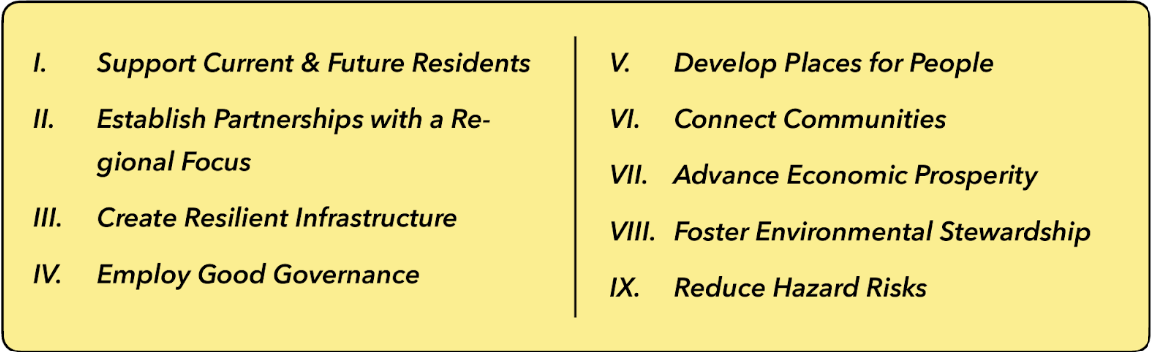

A Road Map

The PLACE Principles provide a roadmap for the development of resilient, environmentally responsible and economically sustainable communities in the face of evolving challenges.

1. Support Current & Future Residents – Everyone should have access to affordable homes, transportation, economic opportunity, representation, social culture, and supportive services. As migration changes social structure, both existing communities and their new neighbors need a broad support network.

2. Establish Partnerships with a Regional Focus – Places are stronger when supported and connected across the region. Coordination among nearby places allows resources to be pooled and benefits to be multiplied, creating a more resilient regional economy overall.

3. Create Resilient Infrastructure – Infrastructure systems like water and waste systems, roadways, agriculture, and energy systems need to be efficient, coordinated, adaptable, and designed for their location and climate.

4. Employ Good Governance – Government should be transparent, agile, accessible, representative, and based on the interest of the public. Issues should be addressed at the most local level possible, be that the block, neighborhood, ward, city, or above.

5. Develop Places for People – Places should be designed and built for people — providing for their physical and social needs — based upon time-tested patterns that respect the environment, conserve land, and preserve places where people can get around without degrading the environment.

6. Connect Communities – Community cohesion is necessary for thriving and inviting places. There must be ample and culturally appropriate public spaces to gather, access to services and education, and opportunities for both current and future residents to participate in civic life.

7. Advance Economic Prosperity – For a strong local economy, it’s necessary to lower the barriers to entrepreneurship, business, and innovation. Starting and growing businesses should be encouraged and supported, allowing more goods and services to be created locally and money reinvested in the community. Places lacking growth and investment should foster new entrepreneurs and incrementally grow their local economies.

8. Foster Environmental Stewardship – Economic and social activities should pursue increasing opportunities to reduce negative and systemic environmental impacts, and in doing so better support local communities through job creation, environmental justice, and long-term economic resilience.

9. Reduce Hazard Risks – Every place has risks — environmental, social, and economic — with many exacerbated by climate change. Communities should strive to be ready for anticipated disasters and support community cohesion as a critical network for managing disasters.

Planning for Climate Migration

Climate migration has already begun and before it accelerates, we must ensure that the resulting growth does not perpetuate the status quo. Left unchecked, migration will increase suburban sprawl and all of its related impacts — physical, social, and fiscal — and their associated inequities.

Luckily, many tools exist to address these impacts. Building in ways that reduce future climate risk, improve public health, support opportunity and local economics, and increase mobility can be addressed through zoning reform, historic and innovative housing modes, green infrastructure, mobility, walkable development, downtown and main street revitalization, and the many other core tools of New Urbanism.

Migration will reshape the built environment around the world by rebalancing population centers, productive lands, and means of transporting people and goods. While early changes will consist of localized movement from one side of town to another, subsequent change will involve substantial movement across state and national borders. Simply put, the US and other countries will be reshaped as a result of climate migration, in a manner not seen in a millennium.

The tools of infill and redevelopment will be critical, alongside new development, entirely new cities, transformed rural and natural areas, and all of the related transportation, utility, and economic systems. We are on the verge of major worldwide reconstruction — now is the time to define its course.

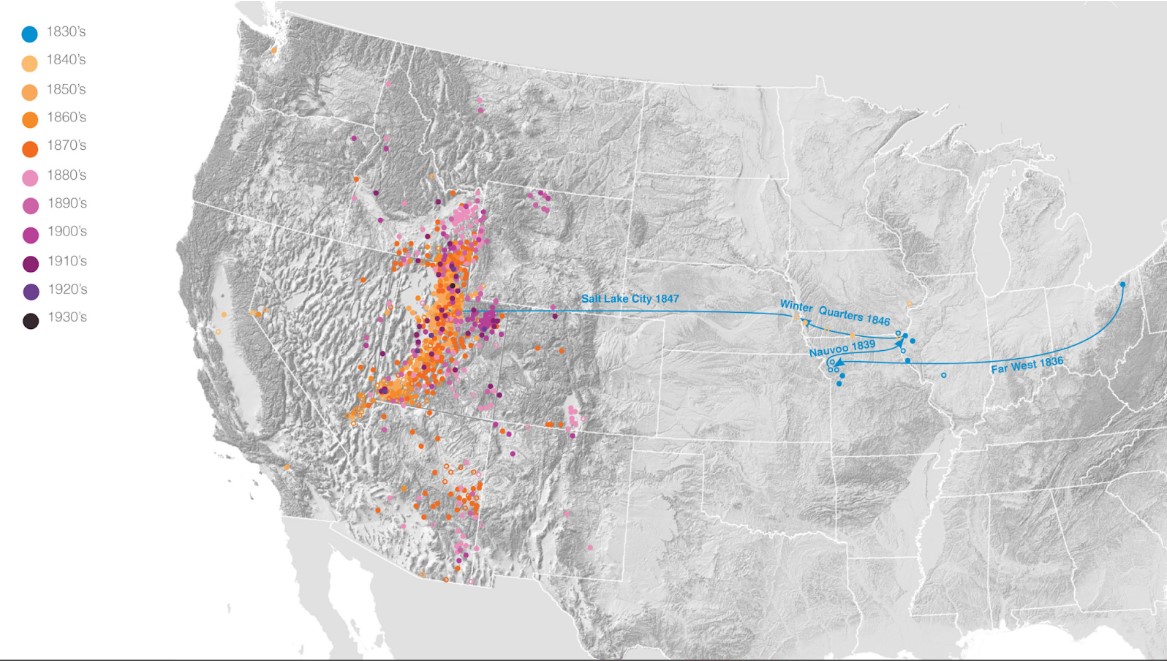

Major population migration and growth isn’t new — nor is building new cities. Take the westward migration of Mormons for example: one of many major migrations in North America alone that established 765 new towns and cities. DPZ studied the Mormon migration and its town building principles, which reflect many aspects of New Urbanism.

Westward migration of Mormons. Map source: DPZ CoDesign.

To further underline the scale of climate migration, consider that the average population growth in North America today is at about net 3.2 million people annually; that is a new Los Angeles or Chicago every year. Unfortunately that growth is not in new towns and cities, but in urban and rural sprawl.

Today’s policies ensure that the growth related to migration perpetuate the suburban condition, which is a serious climate risk. Even in small towns, without action the built and social environment will be eroded, greenhouse gas emissions will continue to increase, and we will lose our increasingly rare, valuable agricultural lands.

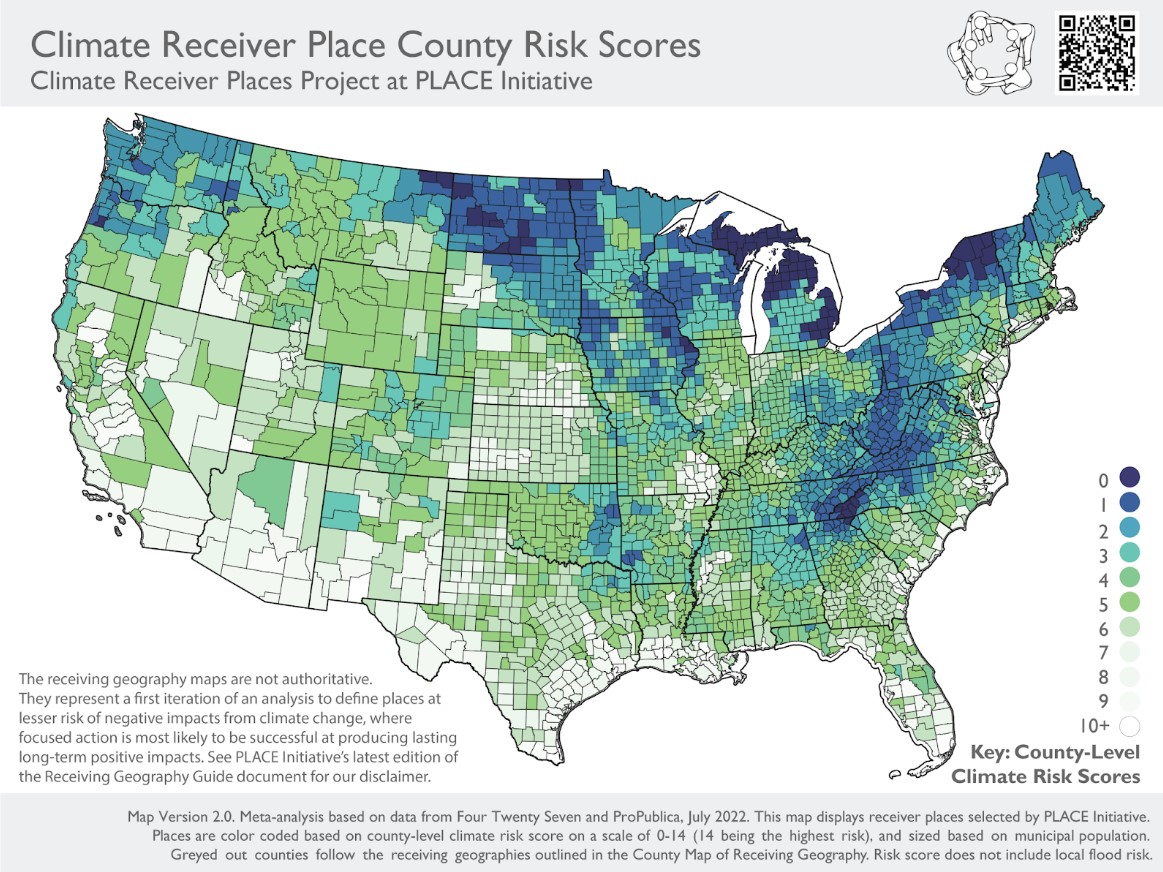

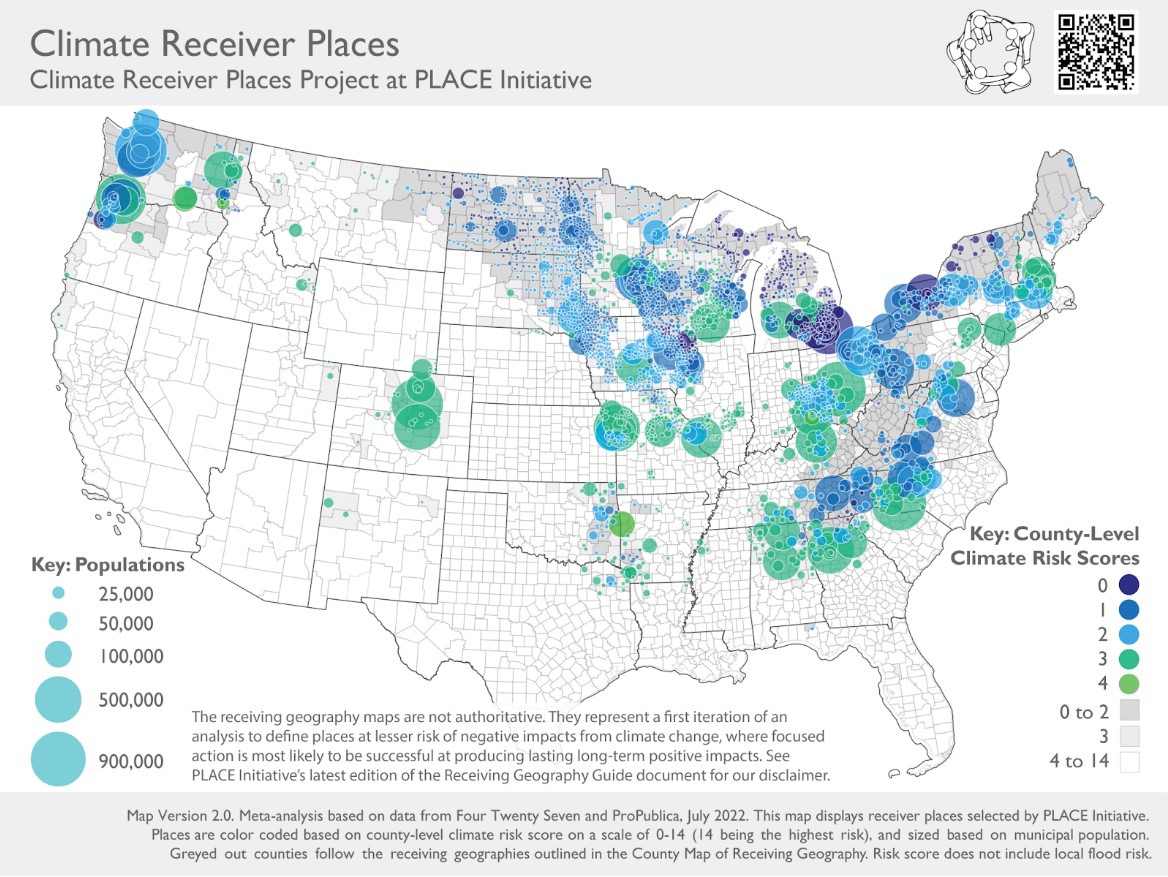

To address the opportunities, PLACE has mapped the likely result of long-term migration in the US in order to focus reform efforts. Locations with the least future risk are our future opportunity zones. Many have experienced population loss in the 20th Century and are open to growth and the work necessary to manifest positive change.

For these places, hope and opportunity offer a new and important approach to climate change. PLACE’s work ties the opportunity of growth with the necessary policy change and programs to build long-term economic and social resilience, tied directly to our work in New Urbanism.

Expanding Our Movement

New Urbanism emerged through the successes and challenges experienced by its founding cohort of professionals — including DPZ founders Lizz and Andrés — newly connected by increased publishing and emerging communications technologies.

With both a reverence for long-lived community building practices and a vision for a better future, leaders crafted clear principles in the Charter of the New Urbanism. With few exceptions, this vision and its related principles remain critically important, especially with increasing climate threats. PLACE believes that many more organizations and individuals are ready to embrace New Urbanism’s principles, provided a fitting framing. Solving for climate and equity through the lens of urbanism motivates a new constituency that will carry forward a commitment to people-centric change. The Charter can coordinate efforts from a broad range of organizations to create resilient regions and equitable places and PLACE endeavors to bring the lens and tools of New Urbanism to the climate space.

These effective solutions are not inherently political. Rather, they require many parallel approaches, with PLACE ensuring that solutions for climate and equity recognize the critical role and interplay of built and natural environments